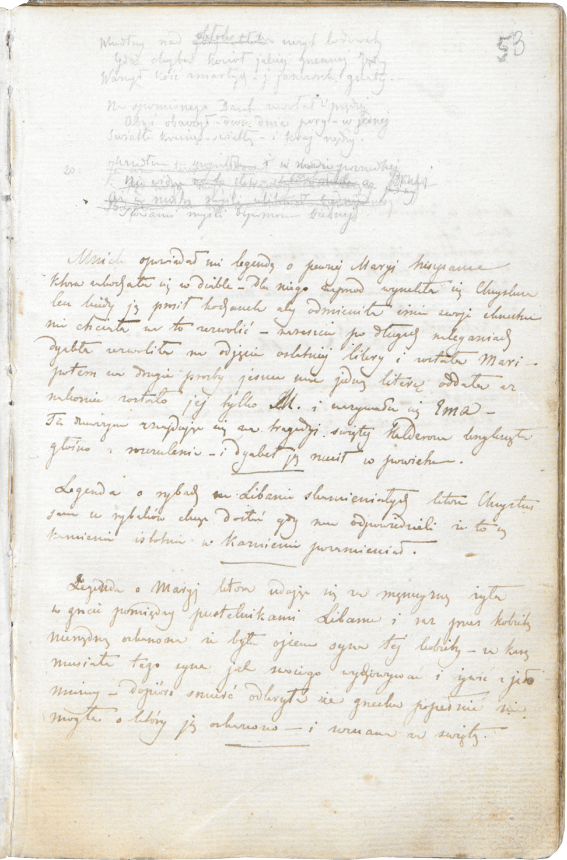

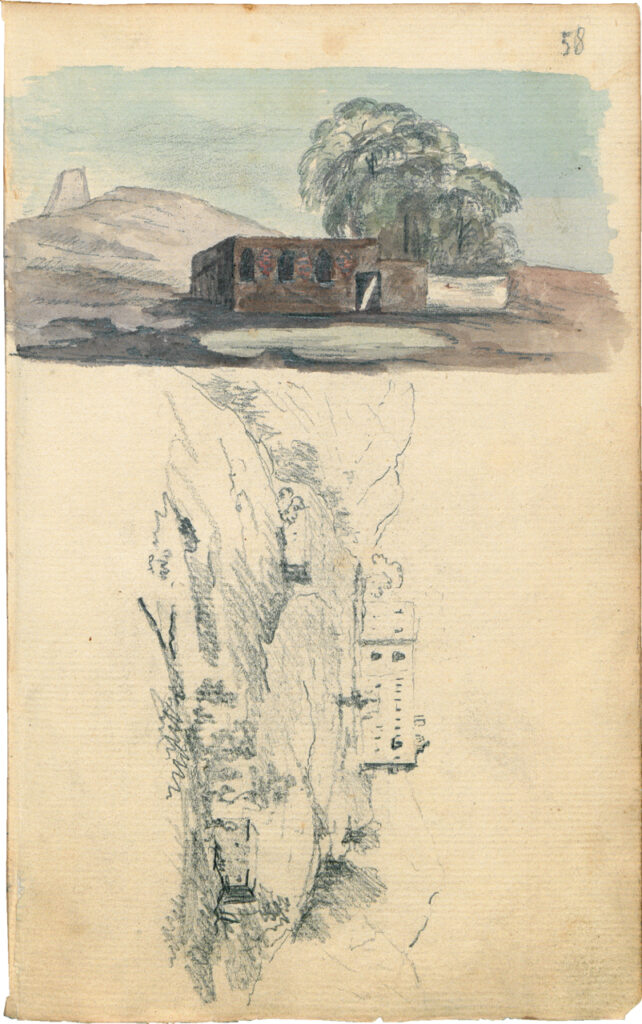

The Betcheszban monastery, a pencil drawing by Juliusz Słowacki from his Eastern Notebook (the Russian State Library in Moscow)

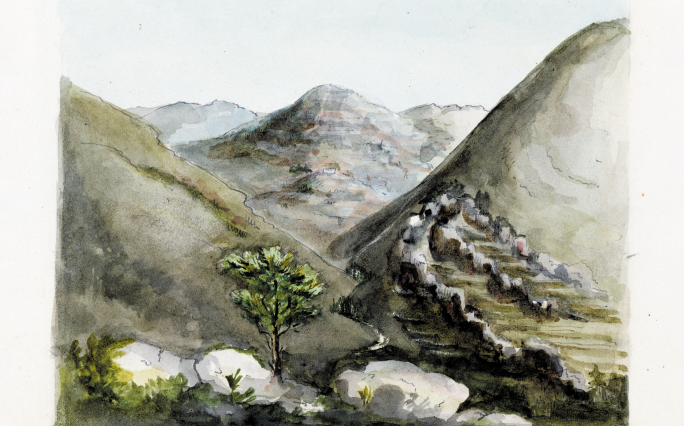

And thus I intend to spend a month or two at the monastery of Bet-chesz-Ban. I shall lead a solitary life there, not unlike the one I had in Switzerland, in the company of some Armenian monks and one painter from Rome, who is working on the paintings for the church. The place I have chosen for my rest is one of the prettiest spots in Syria. I expect that spending some time in quiet meditation will bring me a great deal of pleasure indeed.

A letter by Juliusz Słowacki to his mother, 17th February 1837, Beirut

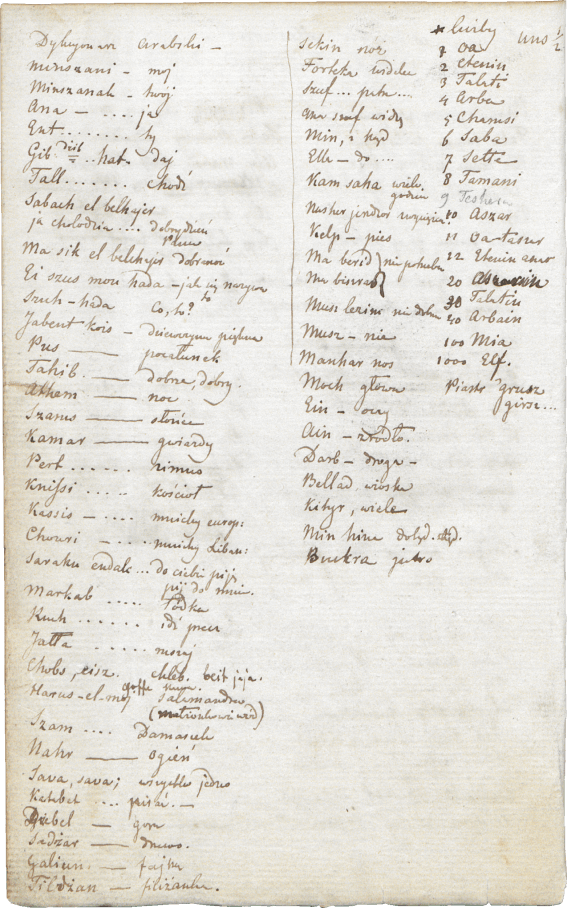

A group of the Druze, a pencil drawing by Juliusz Słowacki from his Eastern Notebook (the Russian State Library in Moscow)

I am now arrived at a country where spring reigns in all her glory: some of the trees have yet to cast off their green mantle, others are preparing to put it on. Almond trees rain with blossoms, the sun is delicious — in short, it is truly the promised land. I intend to stay here until two months have passed. I shall not go to Constantinople as I have little interest in that city; I would rather make a closer acquaintance of Lebanon and the Christian people of the Maronites…

A letter by Juliusz Słowacki to his mother, 19th February 1837, Beirut

I spent all my days in meditation; then at dusk I would walk to a small spring where the village girls came to draw water, and I talked to them in Arabic, though it must be said that all of my Arabic consists of 200 words with no conjunctions or random endings. Oftentimes the Syrian matrones would offer me their hands so that I could check their pulse, mistaking me for a doctor, for in the East every European is considered to be a doctor. It was strangely entertaining.

A letter by Juliusz Słowacki to his mother, 14th June 1837,

written at sea on the way from Tripoli to Livorno

Father Maksymilian Ryłło in Arab attire, a litography after a drawing by Ludwik Samson Bulewski, 1848, the National Library in Warsaw

I spent the Easter day at the monastery. A Jesuit priest came especially to offer himself as my confessor. At first I did not want to accept, but eventually his friendly insistence persuaded me to confess to him all the sins in my life. Yet when I kneeled before him in the grey hour of the morning, yearning to speak out, I weeped like a child, for I was reminded of the years gone by, of my former innocence, of everything that I was later separated from by the passage of long years… After my confession was finished, the priest got up, patted my shoulder and said: “Go in peace: your faith has saved you”.

A letter by Juliusz Słowacki to his mother, 14th June 1837,

written at sea on the way from Tripoli to Livorno

A view of the mountains from the Betcheszban monastery, a pencil drawing by Juliusz Słowacki from his Eastern Notebook (the Russian State Library in Moscow)

A view of the mountains from the Betcheszban monastery, a watercolour by Juliusz Słowacki from his Sketchbook of the journey to the East (the National Ossoliński Institute in Wrocław)

A view of the Jounieh bay from the Betcheszban monastery, a watercolour by Juliusz Słowacki from his Sketchbook of the journey to the East (the National Ossoliński Institute in Wrocław)

Even though the 45 days that I spent in the monastery were rather monotonous, I felt a strange longing upon leaving it. I was faced with a long journey and further wandering, meanwhile the monks were going to remain here, peaceful in their cells. I was strangely envious of the dullness of their lives. I shall never forget what I felt on my last morning, when I awoke to the sound of knocking on the doors, which roused the sleeping monks in their cells. Thus it was on that day, thus it was to be on the morrow, thus it was to be for them forever — meanwhile I was on my way to Beirut, so I could board a ship and set out for Europe, where no one expected me nor I expected anything. I got on my horse. My guides followed with our saddled mules […]. I looked back — I was already downhill, the monastery sillhoutted against the sky behind me, and upon its flat roof I could perceive tiny black figures; they were the monks, bidding me farewell with their eyes.

A letter by Juliusz Słowacki to his mother, 14th June 1837,

written at sea on the way from Tripoli to Livorno